Il corsaro

Giuseppe Verdi

1, 5, 8, 10 April 2018

Sala Principal

With the collaboration of: Agència Valenciana del Turisme

Running time: 2 h

Conductor

Fabio Biondi

Stage Director

Nicola Raab

Set Designer and Costume Designer

George Souglides

Fight Choreographer and Filming

Ran Arthur Braun

Lighting Designer

David Debrinay

New production

Palau de les Arts, Opéra Monte-Carlo

Cor de la Generalitat

Francesc Perales, chorus master

Orquestra de la Comunitat Valenciana

Corrado

Michael Fabiano

Medora

Kristina Mkhitaryan

Gulnara

Oksana Dyka

Seid

Vito Priante

Giovanni

Evgeny Stavinsky

Selimo

Ignacio Giner **

Un eunuco

Antonio Gómez **

Uno schiavo

Jesús Rita **

** Cor de la Generalitat Valenciana

Act I

The Greek island of the corsairs. Aboard his ship, the chief corsair Corrado, who is in exile, laments his existence as a pirate. He shows his determination to fight against the Turkish Pasha, Seid, and is applauded by his men. Meanwhile, alone in her room, his beloved Medora is fearful for Corrado’s fate and she puts her thoughts into words in a mournful song. The corsair arrives and tells her of his battle plans. Despite her fears and after pleading with him not to go, Corrado leaves her to face the enemy.

Act II

The Turkish city of Corone. In Seid’s harem the odalisques pamper Gulnara, the Pasha’s favourite. But she longs for freedom and to return to her homeland. A messenger brings her an invitation for the celebration that Seid is preparing for after the anticipated defeat of the corsairs. Before the banquet, Seid asks Allah for his protection. Once the celebration is underway, a dervish asks Seid for protection after having escaped from the corsairs. Seid accepts and then receives the news that the Turkish fleet is in flames. The dervish reveals his identity: it is Corrado, who attacks with his men. When the battle appears to have been won, the news that the harem is in flames makes Corrado stop fighting and rescue Gulnara along with the other women. Seid takes advantage of this to counterattack. Finally, Corrado is arrested. Impressed by his brave gesture towards her, Gulnara puts in a good word for the corsair, but Seid condemns him to death.

Act III

Seid’s victory is marred by the suspicion that Gulnara is in love with Corrado. She enters and confirms his fears. The defiant attitude of the slave girl fills the Turk with rage.

Gulnara visits Corrado in his cell and gives him a dagger: she has bribed the guards so that he can escape and kill Seid with the weapon. When Corrado refuses to kill the Turk in such a despicable way, Gulnara decides she will do it herself. A storm blows up after she has left. When she returns, she tells Corrado that Seid is dead and offers to escape with him. Corrado accepts and they run off together towards the island of the corsairs.

The Greek island of the corsairs. Medora, in despair from having received no news of Corrado, has taken poison to end her own life. As she lies dying, the corsairs’ ship arrives and Corrado and Gulnara run to the unfortunate Medora’s side, who dies in the arms of her beloved. In despair, Corrado throws himself off a cliff despite the efforts of his men to stop him from doing so, and Gulnara faints.

The two-sided opera

Masculine and feminine; hero and anti-hero; genius and dullness; refinement and roughness.

First performed on 25th October 1848 at the Teatro Grande in Trieste, Il Corsaro is one of the most enigmatic operas by Giuseppe Verdi, with the libretto written by the librettist poet Francesco Maria Piave.

An enigmatic and surprising opera with its rich melodies and the ability to identify moods, something that Verdi constantly describes and emphasises, is free of the fixed forms and meter of the poetry. By evoking nature with the musical notes and timbre of the instruments, on occasions rough and on others refined and with feeling, its correlation of sound lies in the descriptive harmonies and melodies that alternate between the ethereal and arrogant.

As far as the composition is concerned, Il Corsaro has an archaic troubling spirit – a frequent reason for the discredit it received in the past, due to the fact that its dullness makes it difficult, at first, to appreciate the touches of genius which combine with the sparkle of discoveries yet to come. Not to mention the bursts of the vibrant warlike and patriotic Risorgimento and the profound emotions of the psychological descriptions.

This work owes a large part of its roughness, the evocation of the elements of nature, and its uniqueness to its literary origin: Lord Byron’s poem The Corsair. A tale in verse of curiously epic poetry, it is a narrative rather than a dramatic text, which obsessively centres on the moods of the protagonists rather than on the events that condition them. It is a poem with romantic human stereotypes that stand out against Nature, powerful and vigorous, and which simultaneously complement their complex inner nature: two people who are one; a double-sided coin in an intense and mystifying game of asexual bipolarity, the feminine and the masculine.

The protagonists are enlightened by new lights, beneath which, Corrado becomes dehumanised and Gulnara loses the traditional characteristics of her sex. Depending on her attitude, she is the prototype of a woman or the prototype of what is manly. Verdi and Piave loyally keep to Byron’s work, expressing in their Corsaro the intriguing dualism between the romantic hero with an antihero nature and the heroine that ceases to be a victim to become the persecutor.

This is a transforming step for the female character, given the fact that the physical gesture of holding a weapon was a great novelty in romantic poetry, although Verdi recognises it as his own since it was also a feature of previous protagonists of his. This gesture had become an aesthetic characteristic: a kind of female “sterilization” –clearly echoing Shakespeare- in favour of the new heroism of a woman who was offered a place in the world which, until then, she had been denied.

This almost perverse dualism for Byron was the poetic reflection of his own creative bipolarity. But neither Byron, nor Verdi nor Piave forsake the iconic and expected character of a woman, virginal and passive, as seen in Medora the lover and sufferer, whose presence reinforces the Corrado/Gulnara dualism.

Il Corsaro is a narrative musical poem in which the dramatic aspect has many similarities with Wagner’s work: the characters are victims of their personal development and primitive impulses, and not of their situation nor background, which gives them a modern and universal scenic dimension. Not in vain did Richard Wagner and Giuseppe Verdi experience a crucial change in their lives during the symbolic year of 1848, the year of Marx and Bakunin, the year of unions and separations.

Within the poet’s mind

In 1814 “The Corsair” by Lord Byron was published and sold 10.000 copies on the 1st day alone, an unprecedented success for a poem. It is loosely connected to Byron’s own journeys in Greece, but draws heavily on the authors inner personal world and also some of his political views. Verdi was immediately attracted by its romantic emotional power and asked Francesco Maria Piave to turn it into a libretto.

Corrado, the corsair, is fighting all mankind, to free the oppressed, but is suffering from the task he set himself as nevertheless it means war, death and destruction, also to the ones close to himself.

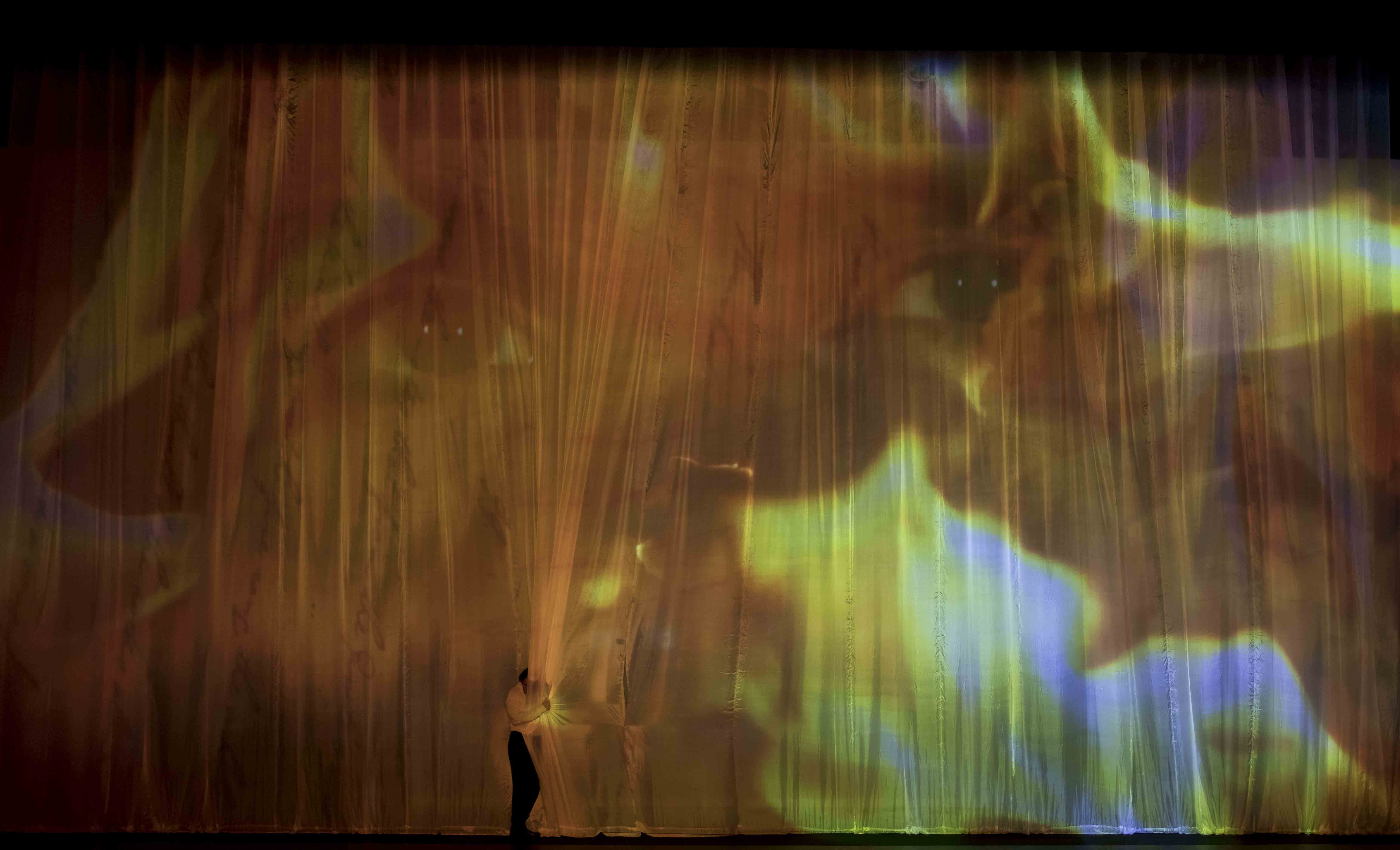

The resulting opera is extremely condensed and concise, less then 2hours of music, and it feels like witnessing the events -despite changes of location from the Corsair’s island to a Greek city under Turkish rule- in real time. The connection between main character and creator of the story seems palpable, and has led us to our decision, to internalise most of the plot. All outer events of action have become either memory or imagination, the poet therefore either reminiscing over his already finished scriptures or actively creating events and characters in his head and bringing them to paper. Finally, he enters his own story and looses himself in it. In the end we could say that we have witnessed the last 2h, -the actual duration of the opera- of the life of the poet. We see and understand the destructive beauty of the process of creation, the dangers of entering into the world of one’s own mind, refusing to ever leave it again.

Nicola Raab

© Mikel Ponce /© Miguel Lorenzo